UNEMPHATIC LAND: On

Frances Cornford’s Poetry

Apocalypse

and After II

by David Hackbridge

Johnson

and Iain Sinclair) please scroll down to where it says ‘older posts’

A trio of Cornford slim volumes

One

of the more surprising inclusions in James Keery’s Apocalypse: An Anthology[1]

is Frances Cornford. Not known in the neoromantic

hothouses of Soho or Fitzrovia, she plied her peaceful trade in verses from the

placid fastness of Cambridge. There she

lived with another Francis, her husband the classicist and occasional poet

Francis Cornford. There doesn’t appear

to be a monograph on Mrs Cornford, although much can be gleaned from Frances

(yes, another one) Spalding’s excellent biography of Gwen Raverat[2],

the poet’s cousin (both were granddaughters of Charles Darwin) and provider of

richly wrought woodcut designs for some of her books. Raverat herself wrote of Frances is her

classic book on childhood Period Piece.[3] Therein is portrayed a life of material ease

thanks to the generous bequests provided by Charles Darwin to his children. The

extended family (Vaughan Willaimses, Wedgewoods and Wordsworths populate the

tree) is notable for having a surfeit of talent, many of its members being

active in scientific and artistic circles.

Despite the outward appearances of a charmed existence, there seemed to

have been a thread of illness carried from generation to generation that

clouded an otherwise serene picture.

Victorian illnesses can resist exactitude – there are several theories

as to what grandfather Darwin suffered from – but with granddaughter Frances

there is more detail available relating to her crushing bouts of depression;

its periodicity as adumbrated by Spalding suggests a bipolar tendency.

Much

of Frances Cornford’s poetry celebrates the unchanging landscape of

Cambridgeshire – its fenland horizons, its animals and trees, together with the

rounds of family life and loves. As

Cornford herself suggests in the title poem of her collection, Travelling Home, she inhabits a ‘sober,

fruitful, unemphatic land’ in which the poet hopes to remain ‘undistinguished’ –

such a desire gently measures the ambition of her verse but should not allow

for her easy dismissal in the light of louder and more flamboyant voices. The poem ends with shadows flowing over a

dyke ‘As the Icenian watched them long ago’[4]

– making thereby kinship with A. E. Housman’s conquering Roman through which

the ‘gale of life’ blew, and whose is now ‘ashes under Uricon’.[5] There is a hint here of a binding fate that

connects the generations, and links them to landscape. Given the largely rural tropes that garland one

of her first books, Poems, and that

it appeared in 1910, just before Edward Marsh commenced his series of five books

each called, Georgian Poetry, it is

perhaps surprising that she wasn’t included in any of the five – apart from the

inclusion of Fredegond Shove and Vita Sackville-West, these were strictly

male-orientated publications. She

certainly knew Marsh – the archives at the New York Public Library and the

Cambridge University Library contain holdings of letters – and in her early

work she holds her own with Marsh’s chosen poets. ‘The Woods of Despair’ could be a brooding

homage to her friend Walter de La Mare:

Blank and bare

Are the Woods of Despair,

On the goldenest summer day;

And grim and grey

The trodden way

That leads, that leads you there.

O often trodden,

Slippery, sodden,

Lonely, loathèd way.[6]

We glimpse a brief vision

of Rupert Brooke, one of the bright stars in the circle of her early life, in

the brief ‘Youth’, subtitled ‘Epigram’:

A young Apollo, golden-haired,

Stands dreaming on the verge of strife,

Magnificently unprepared

For the long littleness of life.[7]

This poem seems to be

called ‘On Rupert Brooke’ in some internet circles together with the implication

that it is a memorial to his early death; the publication date of the volume in

which the poem appears discounts this theory, although it is easy to see how

the poem became a retrospective elegy.

Spalding suggests that the rather more disturbing vision of the poem

‘The Mountains in Winter’ relates to Cornford’s time spent in Bex, Switzerland,

in recovery from a severe breakdown that incapacitated her in 1904 and which lasted

for several years. The poem is a sublime

(in the Burkean sense implying fear and attraction) reflection on the vast

mountains ringing the valley in which Bex sits. The entire poem goes:

Unutterably far, and still, and high,

The mountains stand against the sunset

sky.

O little angry heart, against your will

You must grow quiet here, and wise, and

still.[8]

A later volume of Cornford’s,

Autumn Midnight from 1923, brought

out under Harold Monro’s The Poetry Bookshop imprint, the same publisher responsible

for the Georgian Poetry volumes, brings

a continuation of themes drawn from nature and family life:

When I was twenty inches long,

I could not hear the thrushes’ song;

The radiance of morning skies

Was most displeasing to my eyes.[9]

There is nothing to suggest any desire to respond to the seismic effect of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published the year before in 1922 – rather Cornford broadens her craft with gentle satire in ‘Rhyme for a Phonetician’ and even ballad form in ‘The Princess and the Gypsies’. The book is notable for stunning incipits by Eric Gill, a founder with Gwen Raverat and others of the Society of Wood Engravers.

The aforementioned Travelling Home was published in 1948, within the prime catchment period of Keery’s anthology – he takes ‘Soldiers on the Platform’ from this volume, a poem quite likely written during the Second World War. Cornford earns her keep among more obvious Apocalyptics – D. S. Savage, Henry Treece, J. F. Hendry – with her startling portrayal of the anonymity of doomed soldiery with their ‘bullock faces’ and ‘staring sameness’[10] – bovine imagery that remembers Wilfred Owen’s line, ‘What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?’[11] Keery might have included the two poems that follow ‘Soldiers on the Platform’ since they utilise further Owen tropes. In ‘Casualties’ we sense the morbid erotic of bruises ‘kissed with passion’[12] and the grinding action of ‘a great machine’ that uses ‘this once protected flesh’. ‘Autumn Blitz’ sees Cornford alive to the irony of nature’s continuing, yet mute beauty in the face of ‘human chaos’.[13] These poems succeed in their general relation to the fears and stresses of war; Cornford makes a poem of specifics out of the German Army’s use of Leo Tolstoy’s house, Yasnaya Polyana. Converted to a hospital when the Germans took it over in 1941, the house was damaged by fire and there were reports that the grave of Tolstoy had been desecrated during the brief occupation of the estate. Cornford uses the figure of Judas in the poem to focus her sense of cultural betrayal as the flames eat ‘the honoured wood’. As if meditating further on the misuses of culture, Cornford follows ‘The Betrayer’[14] with a poem in which the question is implied of an ‘enemy alien heart’ as to how beauty, such as that to be found in a Schubert song, could find a place in the minds of those so bent on destruction. Cornford does not insist that an ‘innocent core’[15] is to be found unchanged amid the misery caused by aggressive war. Here is presented the same vile disjunct noted in the behaviour of, for example, concentration camp doctor and mass murderer, Joseph Mengele, who relaxed after a day’s ‘work’ by playing 78s of Schubert and Schumann.

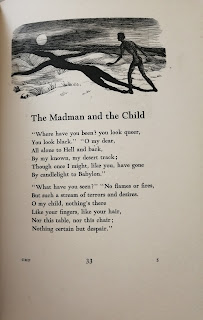

Two pages from Travelling Home – the delicate illustrations are by the poet’s son, Christopher

Cornford

If I have concentrated on

Travelling Home and the poems therein

that support Keery’s inclusion of Frances Cornford in his Apocalypse anthology, there are nevertheless two further books of

hers in my collection that merit attention.

Mountain and Molehills, dates

from 1934 and includes nature poems, recollections of pre-First World War days,

and a number of poems on motherhood that bring to mind Anne Ridler, in that

both poets are able to avoid mawkishness by tender meditations on a sense of

wonder and fragility, that sometimes evoke aspects of religious faith as a

bulwark against harm. The volume is

illustrated by Gwen Raverat in a style that suggests that she and Eric Gill

worked in similarly bold styles of execution.

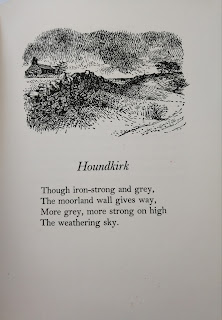

From Mountains and Molehills

with one of Gwen Raverat’s woodcuts

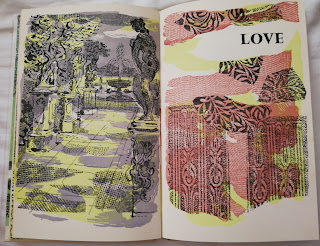

For what turned out to be

her last book (she died during its proof stage) Frances Cornford worked with

her son Christopher to create a poetic-visual feast. For his illustrations in On a Calm Shore, the artist draws from a repertoire of Greek statuary,

printed fabrics, natural forms and abstract designs, to create one- or two-colour

accompaniments to the poems. That the

poet gathers the verses into sections – Time, Children, Night and Morning,

Love, Places and Seasons, and finally, Transience – shows her steadfastness to

those verities that sustained a poetic career of nearly 60 years. Among the many attractive poems there are a

few barbs: the masked guests in ‘A Carnival Dream’ – even the lovers ‘never

could perceive each other’s hidden face’[16]

– brings a flavour of W. B. Yeats to the proceedings; and in the valedictory

‘Exeunt Omnes’ she makes a variation on Shakespeare’s ‘All the world’s a stage’

from As You Like It by reflecting on

the varied parts that people play yet how as ‘the players take their call’ they

‘convey the evanescence of us all.’[17] We might not agree with Cornford that she

achieved that wished for state of being ‘undistinguished’ – her poems have too

many quiet joys for that. And as Keery

shows, she had the claws for tackling, when she chose to, more conflictual

themes that might not otherwise present themselves in the fields of

Cambridgeshire.

That Frances Cornford

grew up among long Victorian shadows with the implied mores of that age and the

assumed allocations of women’s place within it, I feel sure she was aware. Spalding offers a most telling quotation from

one of Frances’ letters to her cousin Gwen, in which she perceives how people

keep up a life that is ‘Victorian and safe’ and render ‘continual violent

things that are always happening (because that is life)’ as mere

occasional intrusions.[18] There is solace-giving in much of her poetry

but she does allow intrusions of the violent; their continual appearance might

have overwhelmed her often fragile state of being. Her work forms kinship with that of her

friends, many of them women, who sought creative outlets away from convention –

Fredegond Shove, Gwen Raverat, Gwen John, Virginia Woolf, and Jane Harrison

among them – and as such her poems take their place within that greater body of

important work.

A double-page spread from On a Calm Shore with Christopher Cornford’s designs

Click below for a reading I made of some

of Frances Cornford’s poems:

[1] James Keery, Apocalypse: An Anthology, London, Carcanet, 2020.

[2] Frances Spalding, Gwen Raverat: Friends, Family & Affections, London, The Harvill

Press, 2001

[3] Gwen Raverat, Period Piece, London, Faber and Faber, 1952.

[4] Frances Cornford, ‘Travelling Home’, Travelling Home, London, The Cresset

Press, p. 9-10.

[5] A. E. Housman, ‘On Wenlock Edge’, A Shropshire Lad, London, The Richards

Press, 1896, p. 45.

[6] Frances Cornford, Poems, Hampstead, The Priory Press, and Cambridge, Bowes and Bowes,

1910, p. 5.

[7] Ibid. p. 15.

[8] Ibid. p. 9. In the late 1990s I lived further up into the

mountains at Villars-sur-Ollon (about 4 miles from Bex). The range of peaks

that includes Dents du Midi, Dent du Morlces, Le Grand Muveran, and Les Diablerets,

is like a cauldron of vast proportions.

Having climbed several of these and nearly falling off the narrow summit

of the Dents du Morcles, I can vouch for the sublimity they inspire.

[9] Frances Cornford, ‘The New-Born Baby’s

Song’, Autumn Midnight, London, The

Poetry Bookshop, 1923, p. 8.

[10] Frances Cornford, Travelling Home, p. 32.

[11] Wilfred Owen, ‘Anthem for Doomed

Youth’, from The Poems of Wilfred Owen

(ed. Edmund Blunden), London, Chatto & Windus, p. 80.

[12] Frances Cornford, Travelling Home, p.

33.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. p. 35.

[15] Ibid. p. 36.

[16] Frances Cornford, On a Calm Shore, London, The Cresset Press, 1960, p. 92.

[17] Ibid. p. 95.

[18] Frances Spalding, Op. cit. p. 304.